Download this Report (PDF, Version 2)

New Power

The idea of power typically has a bifurcated response — equally attractive (don’t you want some?) and yet somehow simultaneously repulsive (to want it is wrong, right?!).

But no one doubts that power matters. When you understand how power works, you understand the world — how resources get allocated, what creates economic outcomes, and certainly how policy is created. Society is shaped by power; by who is able to participate, to what degree they can affect change, and how they participate in the economy. Power thus informs the fundamental conditions for prosperity.

Throughout history, innovations in technology resulted in significant and often unanticipated shifts in the balance of power. The Internet is no different. If knowledge creates power, then the free flow of information surely does something to power. The question is, what?

Many people think social media shifts power when, in reality, there is often more noise than actual new outcomes. For example, the Occupy movement did not disrupt capitalism or “occupy” much. Bring Back The Girls had the support of celebrities and global leaders yet the Girls are still gone a year later. And while the Arab spring was inspirational for many, the political power schema was left largely unchanged. This example proves a key point: we must not confuse the new mechanisms of the social era as a shift in new power. Jeff Pfeffer, Stanford professor and notable author on traditional power, would likely refer to this by The Who verse, “Meet your new boss, same as your old boss.” Sharing, openness, and mass participation are new tactics but they can be used to perpetuate sameness. For example, Uber uses the participation of the many, but the outcome to the majority of those involved is much the same as the old taxi industry. Power itself hasn’t changed; it was once in the hands of a few, and it remains so. For there to be a shift in “new power”, it has to address how “new people” get access to power previously denied.

So, the real question to understand “new power” is: when does the capacity to participate = create a different outcome for those previously underserved?

Example of “New Power”

Let me illustrate what “new power” looks like with a story about a deeply esoteric topic: the art of protein folding.

Until recently, the scientific community had hit a serious snag related to knowing how proteins fold. It turns out that proteins, which are strings of amino acids, don’t spend much time in a linear string-like shape. Their normal state of being is as a three-dimensional shape. Their transformation from string to shape is called “folding.” Proteins that are folded normally will perform their normal healthy biological functions. But misfolded proteins cause disease, such as Alzheimer’s, Sickle Cell Anemia, and ALS. Poor understanding of how proteins fold and misfold was a major impediment to finding cures because each research team had to recreate a fundamental basis before they could study a specific.

Despite significant efforts, protein-folding patterns could not be reduced to a set of rules or software algorithms. Discerning those patterns required human creativity and judgement, which meant, amazingly, that humans are able to do what technology cannot.

A traditional approach of hiring experts to fold thousands of proteins would require finding and financing an army of experts, at prohibitive cost. So, a team of researchers at the University of Washington — Dr David Baker, Zoran Popovic, Seth Cooper, and Adrien Treuille — set out to involve more people towards this effort. They created an online protein-folding game, Fold It, initially envisioning that PhD students in various parts of the world — say India or China — would lend their expertise. The idea was that “crowdsourcing” could be used to get the work done.

Fold It was ultimately successful, but its initial failures turned out to be instructive. When they first started, they were convinced this was a way to get offshore (cheaper) labor. But, “we learned that requiring the ‘players’ to be alert to all the complexities of the science was a super high bar for participation,” said Treuille. There just wasn’t enough creativity in that pool of talent, global though it was. “Then, I was in a meeting with some of the world’s best physicists and realized they actually simplified things, and so that inspired us. We decided to do the same for Fold It. The theoretical stuff wasn’t essential to engage creativity, we realized. What was more important was to let people learn concepts through trial-and-error so they could apply their own, natural problem-solving skills. This got more people engaged, without lowering the quality of the results — at all.”

Next, they observed that progress was better and faster when players helped each other. “We added a point-based incentive scheme to reward collaboration amongst the players. That may not be a big deal as we look back, but we hadn’t designed it that way at the beginning. People were first competing against each other, and we needed to get them to complete against the bigger problem.” Interestingly, this design shift points out how crowdsourcing is not about getting other people to do your work, but about building community. Crowdsourcing without a community will not result in complex solution solving; it will only do simple solutions, something that can be done just as easily with an algorithm. Interestingly enough, people wanted to help one another but felt held back by how they were rewarded for that. It was participants who gave feedback on this “conflict” between the personal interests of the players and the rules of the game.

“Then we noticed,” Treuille said, “that the reward system that created collaboration still wasn’t designed right. We realized that something was causing a distortion. We watched for a while and realized that players tended to give more points to ‘high status’ players — those that were identified with a top tier school, for example — instead of those with the best (better) results. So we tuned it again to hide those social status signals.”

This shift addresses how bias works and adjusts for the consequences of it. What it meant in practical terms is that it allowed people who were previously “uncredentialed” — women, people of color, too old or too young, or from a lower status school — to be equalized by contribution level. Without addressing the blind spots bias raises in all people, it would have left out some of the contributions, perhaps even the crucial ones.

It all paid off. One success of many came in 2011. Over a period of just ten days, Fold It players deciphered the structure of an AIDs-related virus that had puzzled scientists for fifteen years, a discovery that has already helped the development of new medicines. There’s even a database now, roughly a “protein folder’s periodic table,” that is accelerating medical progress.

However, the final lesson of Fold It — a surprise to the UW team — concerned the “winner” of the game — the person who turned out to be the best protein folder in the world. Was it the most credentialed expert? No. Was it the most influential person in the field? No. Was it the most authoritative person leading an existing organization? No. In fact, it was someone who lacked authority, personal influence, and organizational heft. It was a person who — by traditional measures — was powerless.

The best protein folder turned out to be Susanne Halitzgy, an administrator at a rehab clinic in Manchester, England. During the day, she answered the phone but her long-time passion was solving puzzles, such as Rubik’s cubes and Sudoku. She studied medical science early in her career but dropped it in part due to the sexism she encountered. Medicine lost her inherent capacity, at least for a while. But Fold It revealed her power, and enabled it to make a difference.

Lessons of “New Power”

The Fold It example with Susan Halitzgy’s participation represents a new prosperity, as defined by a novel solution to a human problem, operating at scale.

What did you see that enabled a “new power” to come about in the FoldIt story? It’s a question worth exploring.

I admit that, at first, I said that Haltizgy’s power changed. I argued that what she brought to the table was finally able to count. But in further reflection, I no longer believe that’s what’s happening. It was Hilary Austen (associated with MPI) that pointed out that Halitzgy didn’t change at all. Which got me thinking… her intelligence didn’t change, neither did her sense of agency. Nor did she get new knowledge, or become more influential. So, what actually happened?

She got revealed.

Her ability to make a dent (affect change by her participation, the definition of power) changed because of the conditions created by Fold It. In this slow march towards a new outcome, her capacity was unlocked. If new power is the capacity to participate in a way that creates an outcome (by a previously denied party), then it’s the Fold It approach that enables “new power”.

Can this approach be used repeatedly towards other predictive outcomes? Perhaps. To understand that, let’s focus on what exactly Fold It did. At the most obvious level, they are using platforms, networks, crowdsourcing — something that allows many to participate. But what they did specifically different matters. They drew on all available talent, not just the things that matched what they expected to see, and then built a community united in a shared purpose, and then engaged them act as one.

But let’s take that apart some specifically; key distinctions matter greatly if we’re going to repeat the pattern.

First, what Fold It did was to move away from authority power, which required someone with the “right education” to navigate the jargon, or “right credentials” or even “right rank” to be qualified enough. This shift honors the infinite potential of talent around the world, in all sizes, shapes, and colors with different types of intelligence and experience.

Second, they re-aligned everyone against a common purpose, not just commonalities. By accounting for how all humans screen based on some preconceived pattern recognition (aka bias), they shifted the focus. Their construct let the focus be on the best idea for the shared purpose, not the best (or loudest) person we expect to have the best idea. It’s true that ideas have no gender, no race, no disability, sexuality, age, or religion. Yet power sometimes precludes participation of new ideas based on who has them. By focusing on common purpose, not commonalities, those too often left on the sidelines — the young and the old, women, members of the LGBT community, people of color — are able to contribute to the solution. Solutions to some of our more persistent and complex problems are not going to be algorithmic but people-powered.

Third, Fold It shifted the onus of momentum onto the peer-to-peer community. People do amazing things if (a) they believe they can, (b) are connected, and (c) are expected to / rewarded for working together. People work together naturally, to make things big enough to matter, when free from inner conflict. Thus, reward /recognition and clarity of the shared outcome allowed speed of solutions.

The architecture of the Fold It model allowed a kind of new scaffolding of power. The medium of crowdsourcing has been around for nearly 20 years. It’s the how of Fold It community constructs that are the “new power”.

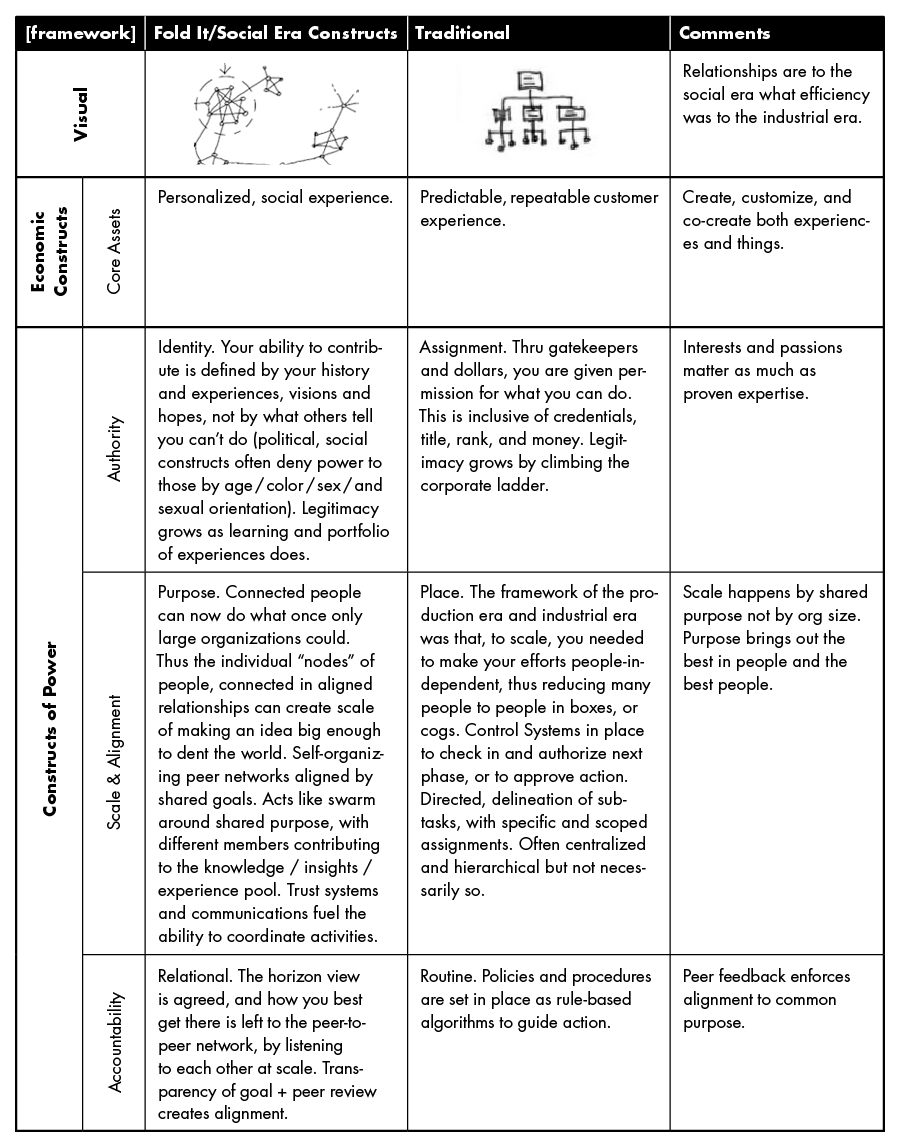

Because this is an organizational construction — what I call scaffolding — perhaps we can look to how this construct is different than prior constructs.

How Different is This Construct?

The shifts: We have gone from a world where value creation was optimized in centralized organizations, to one where it inhabits networks. In the social era, connected people can now do what once only larger organizations could. In authority, people go from needing assignment to having a clear sense of their identity based on their history and experience visions and hopes. Purpose aligns in a way that tasks-delineation fails because it allows for adjustments along the way (without an unnecessary loop of checking back in to get permission). And groups come together in flexible constructs to achieve an outcome with the fundamental belief that the future is not created, but the future is co-created. What drives scale is not the model of replaceable people by the construct to tap into the best of people.

But, this will not happen without policy and decisions — it is a tectonic shift in frameworks. The fine distinctions just drawn from both the Fold It story to the new scaffolding shows how power has changed. In the ways that authority, alignment, and accountability take place differently, we can see the specific shifts at play.

The Pivotal Element: Onlyness

Embedded in the Fold It story, and distinctions drawn in the chart above is how people contribute value in this networked world. I’ve characterized this fundamental unit of value creation, already, in a 2012 Harvard-press published book entitled 11 Rules for Creating Value in the Social Era as ‘Onlyness’.

Onlyness: each of us is standing in a spot only you’re standing in. It’s a function of your history and experiences, visions and hopes. It is the source of original ideas, that when connected to an extended community in shared purpose, scales to make a dent.

It is Kimberly Bryant, who started Black Girls Code because she believes that you either “code or be coded.” Having already trained 3,000 kids through the network of mothers of black girls, she’s working to rebuild the tech economy with a more diverse workforce. In claiming black as a positive imperative, she’s changing the formulation of agency in the black feminine community.

It is Ryan Andreson, Zach Wahls, and Pascal Tessier, three kids who first felt deeply alone and ostracized because of their LGBT association. Each of their loneliness was halted when they found each other and joined with hundreds of thousands of supporters to convince the Boy Scouts to change their discriminatory practices, shifting policy nationwide.

It is, of course, global in nature. It is Ushahidi, a platform started by four bloggers to save lives by steering people away from danger spots and towards safety in a time of Kenyan national unrest. Since then, the Ushahidi platform has been used many times: to guide people to safety when terrorists attacked the Nairobi Westgate Mall, to track radioactive leakage from the Fukushima disaster in Japan saving 100,000 lives, and to capture and track gender-based violence in Pakistan. Of course, its use goes far beyond war zones: as it was once used to clear snow in Washington D.C. Ushahidi does not authorize how the platform is used, but leads an annual process of goal envisioning with over 1500 people engaged at varying levels and then asks that anyone do what they think is best. Accountability is through the network, not controlled by a point of origin.

Onlyness represents a remarkable shift from existing power structures. Power has traditionally been vertical, while potential horizontal. At the intersection lies onlyness. It taps into the existing capability. Like a water table below the surface of the earth, onlyness is always there and if the scaffolding is set up correctly, the economy can tap into it.

Notably, this is not individual power, but power in purposeful communities. Onlyness is not about the individual as the primary player, but how an individual is deeply connected with a community of others like them. Onlyness says why each “node” matters: it enables each of us to step out of geographic, family, or other forms of “local” connections to find those that are actually like-them, based on what matters. It is because of this connected architecture that forms the “new how” for one to bypass gatekeepers and existing power constructs. Onlyness therefore represents an untapped potential, because it lets anyone contribute. Not that everyone will, but that anyone can.

Studying New Power: The scope of this Fellowship

All these examples represent a new prosperity, as defined by new solutions to human problems, operating at scale. New people have the ability to contribute and create new solutions. You can see why, when Roger Martin asked me to participate as a Fellow to study this further alongside community of thinkers pursuing a new prosperity, I joined.

When we can understand how to scale onlyness and the scaffolding that lets that new architecture exist, we will benefit our economy in both financial and social ways.

The next step is to study more examples. They might look like entrepreneurship or technology releasing untapped potential or even social media-driven activism but when studied closely, we’ll find those that unlock new forms of authority, scale, and accountability. They will have the patterns we’ve already seen: agency enabled, alignment in purpose, accountability in the network.

By doing so, we’ll be answer the subsequent questions:

- What are the conditions that allow onlyness to thrive and scale?

- What does that mean for existing institutions and new ones?

- And what can be done to leverage it to expand prosperity?

To do that, we’re going to have to keep digging into key distinction: What defines capacity? What is an outcome? How this is different than existing forms of power? What distinctions cause some things to be simply noise and when it allows a new idea to make a dent? So there is much needed to understand the gap between an “Occupy” that fails in new results and what Fold It was able to do, (as is Patients Like Me, or TEDx, or Ushahidi). The key is to decode models that are creating actual new outcomes that were previously not possible in existing power models. And to make the distinctions between the “how” and the “what” so we can draw much better implications. But more importantly, we can understand what is required to support the “new power” infrastructure.

I imagine what would happen if the lessons from Fold It and Susan Halitzgy could be applied to other things? Who could contribute? What could they create? What new problems might we solve? What new opportunities could we open? What kind of prosperity would it generate? (What could you do?)

And if that excites you, too, I hope you’ll get in touch and join me in chasing this question.