Class is more than a socio-economic construct; its divides are inscribed on the geography of cities and metro areas.

Just as the rise of the knowledge economy has created a job market that is split between high wage knowledge jobs and lower wage service jobs, middle class neighborhoods have been hollowed out as the geography of cities and metropolitan areas has become increasingly divided between rich and poor neighborhoods. Recent research shows that Canada’s major metro areas, notably Toronto and Vancouver, have fallen victim to these urban class divides.

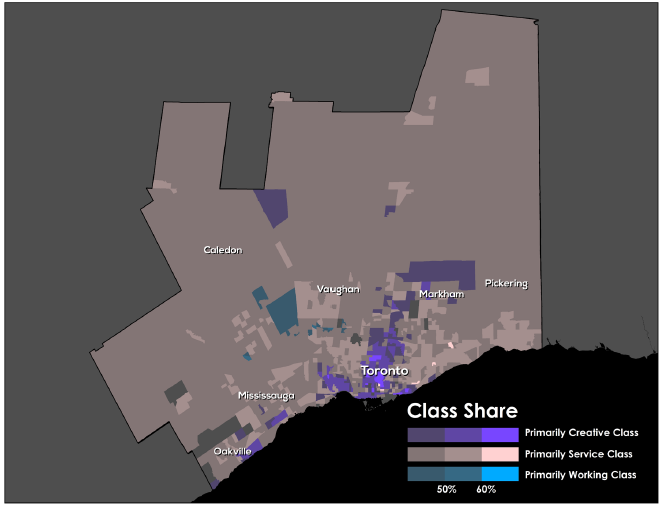

Exhibit 1: Toronto Metro

This Insight supplements the recently released Martin Prosperity Institute (MPI) report, The Divided City, by charting the class divides for Canada’s three largest metros: Toronto, Vancouver, and Montreal. Its maps, based on Statistics Canada 2006 Census, show the residential locations of the three major socioeconomic classes by census tract — the high-pay, high-skill creative class, or people who work in technology, science, media, business, finance, medicine, the arts, and academia; the service class, who work in low-pay, low-skill jobs in retail sales, food handling, home health assistance and the like; and the dwindling blue collar working class.

The colors on the maps reflect the class make-up of census tracts. Predominately creative class tracts are purple, service class tracts are beige, and working class tracts are blue.

In Toronto, the creative class clusters at the urban core, around universities and colleges, across the waterfront, and along major transit routes, especially the Yonge-University-Spadina Subway line. The service class is pushed out to the periphery. There are only a few blue working class tracts in the entire metro.

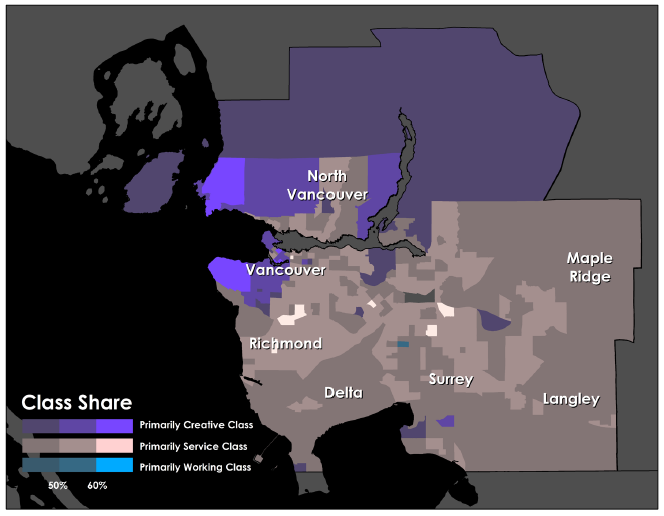

Exhibit 2: Vancouver Metro

In Vancouver, the creative class is clustered in and around the urban core and the waterfront and also forms a huge wedge to the west and the north around natural amenities like parks and mountains. The class divide in the city is west-east, with the service class pushed toward the east and south. There is just one primarily working class tract in the entire metro.

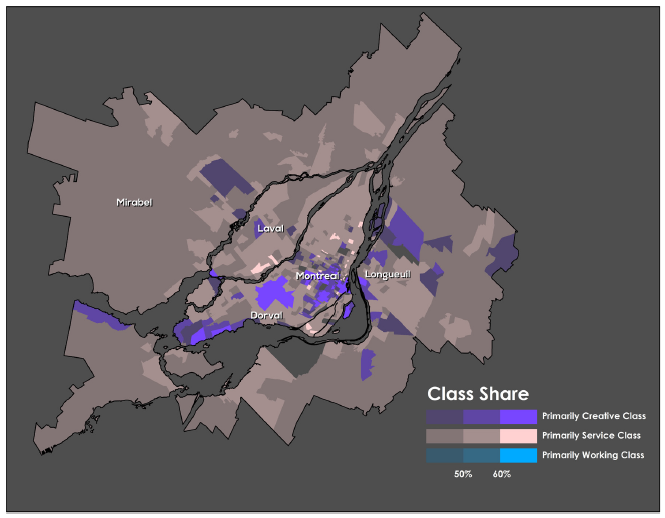

Exhibit 3: Montreal

In Montreal, the creative class also clusters around the urban core, especially on and around Mont-Royal, home to the Université de Montréal. The creative class is also clustered west of the city in the Westmont and Notre-Dame-De- Grâce communities, which are well served by transit and where Concordia University is located. Once again, the service class is pushed to the spaces in between the creative class clusters and to the peripheries, especially in the former industrial communities of Montreal Est and Nord, which are poorly serviced by transit. There is not a single tract in the metro where the working class makes up a plurality of residents.

In all three metros, the creative class clusters around the urban core, near transit, around universities and knowledge institutions, or in proximity to water, parks or mountains. Across all three, the creative class is dominant in the center city and the service class is pushed to the periphery or the spaces between creative class clusters, while precious few working class neighborhoods remain.

The clusters of the creative class are much less concentrated in Canada’s three largest metros than they are in their U.S. counterparts. In Canada, the creative class makes up more than half of the population in just 10 to 15 percent of census tracts—13 percent of Vancouver’s and Montreal’s and slightly less than 10 percent of Toronto’s. In the United States, by way of contrast, the creative class makes up more than fifty percent of the population in a third of all census tracts in Boston and San Francisco and more than 45 percent in Washington, DC.

Conversely, the service class is more segregated and isolated in Canada’s three largest metros. In Vancouver and Montreal, the service class makes up more than fifty percent of the population in fully half of all census tracts. This is higher than any of the U.S. metros we examined in Divided City. All in all, over 80 percent of the tracts in Canada’s three largest metros are primarily service class, considerably more than in comparable U.S. metros.

Canada’s substantial urban class divides reflect an evolving geography of concentrated disadvantage juxtaposed with concentrated advantage, which was at least a partial factor in the rise of Rob Ford’s dysfunctional populist regime in Toronto. This class divergence—and especially the increasing economic and geographic marginalization of the service class—will continue to erode social cohesion and may well portend an even harsher backlash in the future.

Download this Insight (PDF)