Download the Executive Summary (PDF)

Download the Report (PDF)

Executive Summary

Canada is having a moment.

In a world where talent is mobile and technology central, Canada stands out more than ever with its vibrant democracy, growing tech clusters, and unparalleled openness to the world’s migrants.

Yet there is a problem: Despite the nation’s many strengths, Canada’s economy faces serious structural challenges, including from an aging population and slowing output growth. Even more important, the nation needs to ask urgently whether it possesses the right mix of industries performing at a high enough level to allow for new levels of prosperity.

And here, the nation, its provinces, and its local economies need to focus anew on expanding a particular high-value subset of “advanced industries.”

As defined by Brookings, advanced industries—which include industries as diverse as auto and aerospace production, oil and gas extraction, and information technology—are the high-value innovation and technology application industries that inordinately drive regional and national prosperity. As such, advanced industries matter because they generate disproportionate shares of the nation’s output, exports, and research and development.

And yet, for all that, questions surround the state of Canada’s advanced sector.

True, the sector is in many respects well-positioned to compete for market share in the global scrimmage to create value. And yet the fact remains that, at least in comparison with its American counterpart, Canada’s advanced industries are not realizing their full potential, with ramifications that promise slower growth and a declining standard of living for Canadians.

Which is where this report comes in: Intended to help leaders focus their efforts on what matters most in their drive to improve the long-term prospects of the Canadian economy, the following pages provide a framework for targeting ongoing work to build a more dynamic advanced economy that works for all. Along these lines, the report advances three major findings:

1. Canada possesses a diverse, widely distributed, and quite promising advanced industry sector.

An analysis of the size, geography, and growth of the Canadian advanced industry sector shows that:

Canada’s advanced industry sector anchors the nation’s high-value economy.

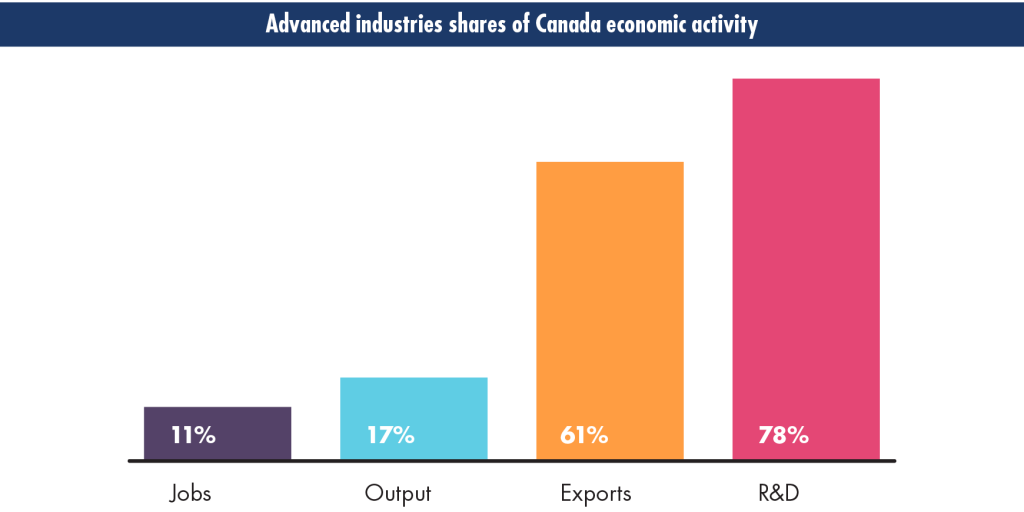

High R&D, high-STEM advanced industries are the bedrock of Canada’s high-value economy. About 1.9 million Canadians worked in advanced industries in 2015, good for about 11 percent of the nation’s employment. From this relatively small share of jobs, however, advanced industries generated 17 percent of Canada’s GDP, 61 percent of national exports, and 78 percent of research and development. These outsized shares reflect that the average value-added per employee in advanced industries was 34 percent higher than in the economy overall. High productivity within the sector ensures that the average worker employed in an advanced industry earned a yearly wage nearly 50 percent higher than the average Canadian worker.

Advanced industries anchor Canada’s high-value economy

Canada’s advanced industry mix is quite diverse—and changing.

As of 2015, the 50 advanced industries in Canada employed nearly 1.9 million workers and generated $247 billion in output. As such, the sector has notable specializations. In terms of employment, services account for just over half of the Canadian advanced industry worker base (51 percent), followed by manufacturing (36 percent) and energy (13 percent). The impact of the Canadian energy industry, however, becomes apparent in the output statistics. The three advanced energy industries account for 42 percent of national output, led by $67 billion generated by oil and gas extraction alone. Advanced services and manufacturing, meanwhile, each account for 29 percent of national output. In terms of both output and employment, then, Canada’s advanced industry mix skews toward energy when compared to the United States.

With that said, Canada’s advanced industry base has undergone a notable transition since 1996. In that year, advanced manufacturing accounted for over half (52 percent) of the nation’s advanced industry employment while services employed only about 34 percent of advanced industry workers. Incredibly, those shares essentially switched between 1996 and 2015. Tremendous growth in advanced services employment and a slight decline in advanced manufacturing employment fueled this transition.

Province | Total | Manufacturing | Services | Energy |

| Ontario | 805,823 | 344,838 | 402,267 | 58,717 |

| Quebec | 431,971 | 177,435 | 219,418 | 35,118 |

| Alberta | 283,809 | 49,198 | 135,213 | 99,398 |

| British Columbia | 197,038 | 46,122 | 131,577 | 19,339 |

| Manitoba | 50,601 | 24,314 | 15,941 | 10,346 |

| Saskatchewan | 40,321 | 11,696 | 16,452 | 12,172 |

| Nova Scotia | 29,496 | 7,738 | 18,139 | 3,619 |

| New Brunswick | 22,930 | 5,877 | 11,773 | 5,280 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 18,309 | 1,558 | 7,984 | 8,767 |

| Prince Edward Island | 4,373 | 1,766 | 2,276 | 330 |

Canada | 1,884,671 | 670,541 | 961,042 | 253,088 |

Advanced industry employment, by province, 2015

Canadian provinces and metropolitan regions vary significantly in the scale, intensity, and diversity of their advanced industry sectors, which in some ways compare favorably to that of the United States.

Every part of Canada can lay some claim to the nation’s advanced industry economy, albeit at varying scales and intensities. Not surprisingly, Ontario, Quebec, Alberta, and British Columbia loom large, together accounting for 91 percent of Canada’s advanced industry employment.

Ontario alone accounts for 43 percent of the sector’s footprint nationally with over 800,000 advanced industry jobs. As context, Ontario houses the largest concentration of advanced industries employment in North America outside of California and Texas, the respective homes of the United States’ largest technology and energy clusters.

Diving below the provincial level reveals further notable geographic patterns. Not unexpectedly, Canada’s largest Census Metropolitan Areas (CMAs) contain the largest number of advanced industry jobs. Toronto leads the nation with 384,000 workers in advanced industries, followed by Montreal (260,000), Calgary (138,000), and Vancouver (134,000). Together, these four CMAs account for nearly half (49 percent) of Canadian advanced industries employment.

Canada’s most advanced industries-intensive CMAs rival the highest employment shares in the United States. As the home of Silicon Valley, no metro area in North America has a greater share of employment in advanced industries than San Jose (31.4 percent). But notably, the next four metros are Canadian, led by Calgary, Windsor, Kitchener-Waterloo, and Saguenay.

In terms of growth and change, nearly every Canadian CMA added advanced industries employment between 1996 and 2015, with the exception of St. Catharine’s-Niagara, Greater Sudbury, and Thunder Bay. Western and eastern CMAs experienced the fastest advanced industries growth since 1996. Partly driven by the investments in energy, and energy-related manufacturing, metro economies like St. John’s (4.2 percent annualized growth), Saint John (3.6 percent), Moncton (3.4 percent), and Calgary (3.4 percent) experienced the fastest annualized yearly growth in advanced industries employment, albeit several of those from a small base.

But even as local economies added advanced industry jobs on net, the erosion of manufacturing employment took a toll. Ontario metro areas like Oshawa, Hamilton, and Greater Sudbury all saw their share of employment in advanced industries plummet by 20 to 25 percent.

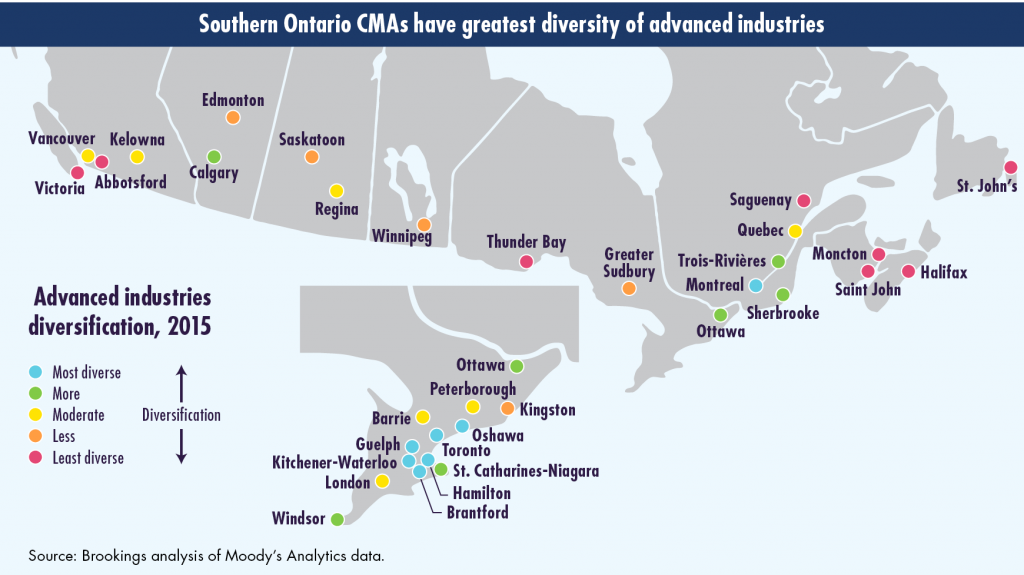

Even with these declines, however, Southern Ontario remains a hub of advanced industry employment, notable for its diversity. We gauge advanced industry diversity by measuring the number of advanced industries in which a metro area has a greater concentration of jobs in a particular industry than the nation as a whole.

By this metric we observe a diversity of advanced industries—particularly in the advanced manufacturing segment—in several Canadian metro areas, led by Kitchener-Waterloo (specialized in 31 of 50 advanced industries), Montreal (26), Toronto (26), Brantford (25), and Hamilton (23). This diversity compares favorably with that in the most diversified advanced industries bases in the United States, like Charlotte (25), San Francisco (24), Chattanooga (24), San Jose (23), and Chicago (23). In all of these places the convergence of digital, genetic, and analog enterprise holds out the possibility of especially valuable new innovations.

Advanced industry diversity, by CMA

2. Advanced sector productivity and productivity growth are much lower in Canadian metro areas than U.S. metro areas

And yet, while Canada’s advanced industries sector compares favorably to its American counterpart, such a comparative lens also reveals a serious problem: Advanced industries in Canada are much less productive than in the United States, with major implications for the nation’s future. Several takeaways arise:

Canadian advanced industry productivity growth has been seriously lagging.

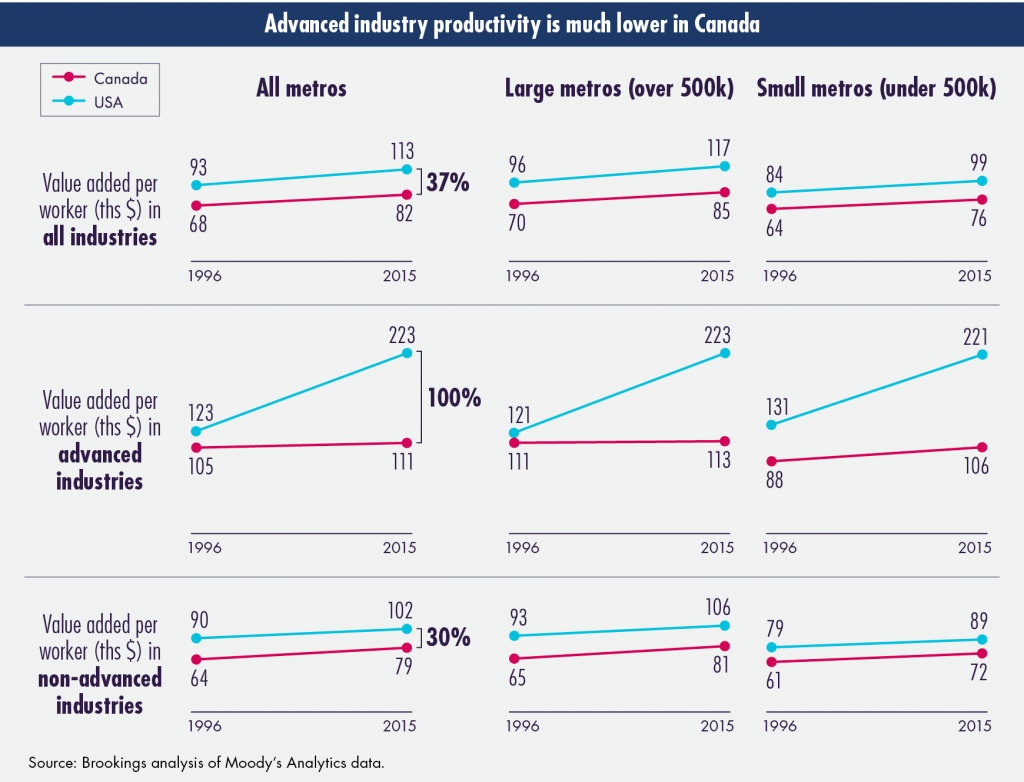

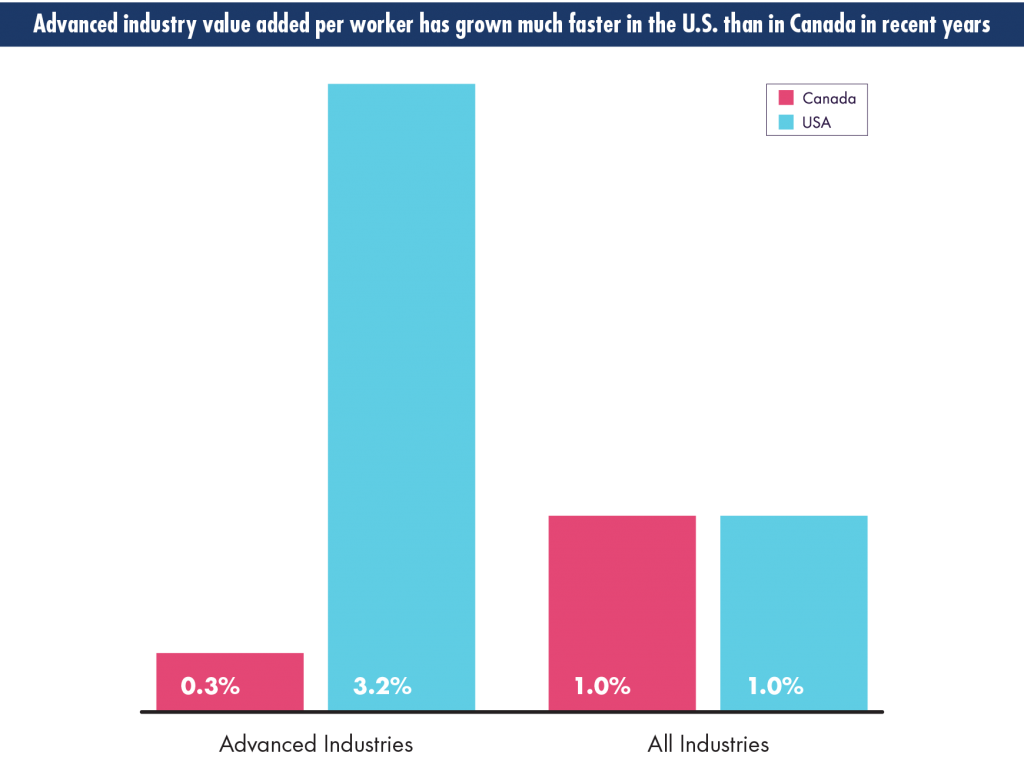

Above all, it is clear that the Canadian advanced sector has failed to respond to the global productivity challenge, at least relative to the U.S. sector. To see this, consider that between 1996 and 2015, U.S. average annual value added per worker growth in advanced industries averaged 3.2 percent per year, while Canadian productivity growth in these industries averaged 0.3 percent. Or, to put it another way: In 1996, the productivity differential between the average Canadian worker in a metro area and the average U.S. worker in a metro area was about 17 percent. By 2015, that gap had grown to 100 percent. In non-advanced industries, meanwhile, Canadian productivity converged with the U.S. between 1996 and 2015.

Thanks to its productivity shortfalls, Canada’s advanced industry sector is depressing the overall productivity of the nation’s regions.

The average value added per worker of all workers in Canadian metro areas is about $82,000, 37 percent lower than the $113,000 per worker figure in the United States. However, given that advanced industry value added per worker languishes at just half the level in Canadian metros as in U.S. ones, it’s clear that advanced industries are inordinately contributing to the nation’s regional productivity deficit.

Behind these trends lie authentic productivity deficits rather than differences of industry structure.

In this regard, the deterioration of Canada’s per-worker advanced sector output since 1996 extends across the vast majority of advanced manufacturing, services, and energy industries. The productivity gap in advanced industries did not arise, then, because Canada’s employment shifted into lower productivity industries. Rather, the differences in productivity growth between Canadian and U.S. metro areas result from advanced industry productivity having grown three times faster in U.S. metro areas. In other words, the differences in productivity between the two countries do not stem from different industrial structures.

Canada-USA productivity gaps, by metro size

Value added per worker growth, 1996–2015, annualized, all metro areas

3. Canada should commit to address four particular sources of its deficient advanced-sector productivity growth, including issues involving the nation’s capital availability, competition levels, connectivity, and technological complexity (the four “Cs”)

Given the sector’s combination of critical importance and lagging productivity, then, Canadian leaders should focus urgently on leading explanations of that lag and seek to address them.

Along those lines, this report—without trying to be comprehensive—assesses four potential causes of Canada’s advanced sector productivity gap, at varying levels of detail, and suggests for each high-level strategic priorities for driving the Canadian advanced sector onto a higher growth path. In keeping with that, Canadian government and business leaders should:

Commit to capital deepening:

Significant previous research has documented that Canada makes do with substantially lower capital intensities across its economy than the United States. This gap depresses productivity growth. Specifically, Canadian firms appear to invest much less than American companies in physical and knowledge capital, such as information and communications technology (ICT), and young Canadian companies enjoy much spottier access to risk capital for innovation and growth. In view of this, public- and private-sector leaders should expand ongoing efforts or develop new initiatives to:

- Promote digital adoption by building awareness of under-investment, especially in ICT, as a competitive problem

- Incentivize greater risk capital investment by helping increase the number of top-performing

venture capital funds - Develop a public-private Canadian Matching Fund and an entirely private Business Growth Fund to provide capital to and take equity stakes in or provide loans to high-promise small- and medium-sized enterprises

Commit to expanding competition:

Competition, in this regard, remains a critical spur to innovation and productivity growth. However, many of Canada’s largest sectors (such as finance and telecommunications) remain highly regulated and more shielded from global competition than firms in the United States. Meanwhile, the nation’s top managers are often trained in those same sectors: strong industries with blue-chip companies that are also highly sheltered. All of which makes it critical for the nation to embrace competition as a source of productivity gains. In this fashion, policymakers should:

- Allow greater market competition in Canada’s highly regulated network sectors

- Promote a business culture of risk-taking by emphasizing entrepreneurship in training and education

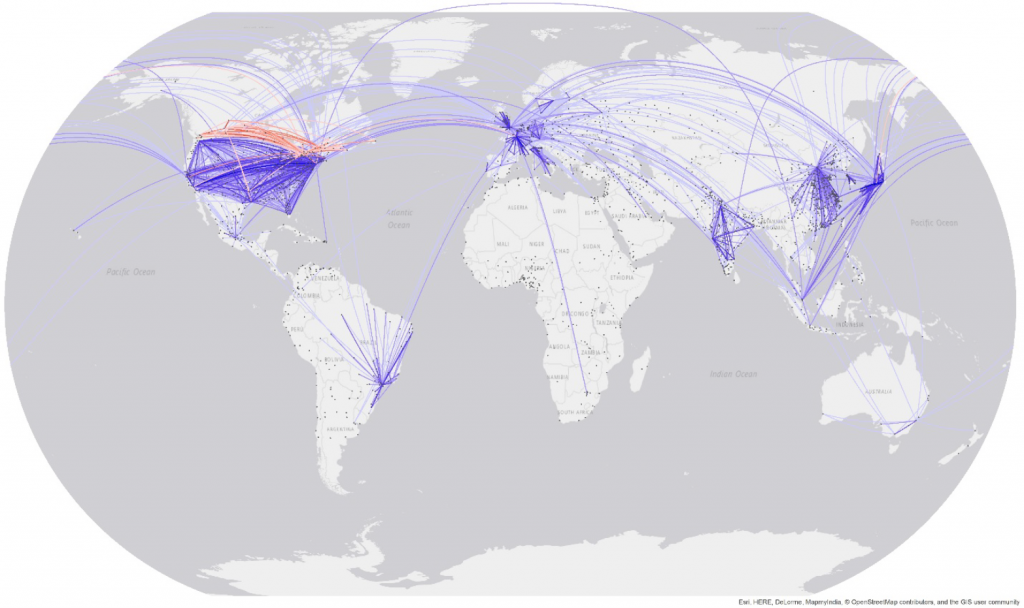

Commit to connectivity:

In addition, new evidence presented in this report adds to concerns that Canada contends with a dearth of large, successful, and globally networked companies in the advanced sector. With too few of these global champions, the nation lacks access to key sources of knowledge, best practice exchange, organizational capacity, and power—all deficiencies that align with its productivity lag. And so the nation should strive to build more globally competitive advanced industry firms in Canada as a way to alter its current branch-plant identity. To that end, leaders should:

- Make scaling up domestic companies a focus of the innovation ecosystem

- Promote foreign direct investment

- Invest in globally connecting infrastructure—especially major international airports

- Support globally relevant institutions such as major research universities

Commit to complexity:

With new research pointing to the association of local economic variety with growth, Canada and its regions should experiment with “complexity analysis” and “smart specialization” as tools for identifying local technological trajectories and projecting smart development strategies. Because technological complexity improves the potential for new innovation, assessing the complexity of local innovation patterns allows for regions and nations to forecast promising developments and then focus and align interventions. In keeping with that, regional economic development leaders—in league with their provincial and federal partners—should adopt smart specialization as a useful strategic framework for improving the efficiency of innovation and the productivity of Canadian regions. To that end, policymakers and business people should:

- Build up data and analytics capabilities that inform policy making at the local level

- Identify regional strengths and align policies and investment that enhance them

- Test network-building policies such as the “supercluster’ initiative and expand where appropriate

- Monitor and adopt global best practises such as the European Commission’s Smart Specialization approach to regional development

Global network of top 500 firms highlighting Canada

For more information on this report:

Mark Muro

Senior Fellow

Metropolitan Policy Program at Brookings

[email protected]