The following research project was completed over the summer of 2016 in New York City through a partnership with the Urban Lab at the NYUSPS Schack Institute of Real Estate. The opinions expressed here represent the work of our two interns, under the supervision of Richard Florida, Shauna Brail, and Steven Pedigo, and do not necessarily reflect those of the Martin Prosperity Institute.

Download this Report (PDF)

Arts institutions, such as prominent, established museums and galleries, complement the inherent heterogeneity and the definitive dynamic mix of urbanity.1 As civic anchors, they are institutional entities that occupy sizeable amounts of land,2 real estate and social capital.3 Anchor institutions have an interdependent relationship with the communities they’re located in, interacting in various capacities such as service providers, workforce developers and community infrastructure builders. Anchor institutions drive shared value for both the institution and the neighbourhood.4 As destination landmarks that denote world-class status, these institutions are magnets for high profile investment, creating pockets of increased real estate values across the city.

Parallelly, investments into cultural anchor institutions fuel new development and encourage the settlement of high-income residents back into the city centre.5 This forces land values to skyrocket, creating shortages of available land and affordable housing options, while native low income individuals are displaced and pushed into the outer suburbs — one of the defining elements of gentrification.

Projected data anticipates that by the year 2050 more people will be living in urban rather than rural areas;,6 as this urban migration continues, the tension for space will persist in superstar global cities such as Paris, London, and most definitely New York. New York City is often the backdrop for the dynamic trends of urbanization facing contemporary cities as one of the world’s most influential economic and cultural nodes. As the home of over 83 museums7 dispersed among its 5 boroughs, the headquarters of some of the world’s most celebrated fashion designers and a plethora of studios and artist-run spaces,8 New York’s dominance as a crucial center of the arts is derived from its dense concentration of creative and cultural producers.

Perhaps New York’s greatest strength lies in its capacity to harness its artistic talents such that they contribute to both the local cultural economy as well as the global marketplace.9 In 2015, 10 of the most expensive works purchased in auction were acquired in New York and the city was the site of two thirds of auction sales over $1 million, highlighting it as a marketplace for the elite.10 For independent artists, New York offers several opportunities to network with the global art world through the annual Armory Fair and Frieze New York.11 This duality solidifies New York’s position on the top of the global art scene while simultaneously acting as a tastemaker for up and coming artists.12

A great deal of work has been dedicated to highlighting the specific role that arts institutions in New York have played in neighbourhood change. Through their symbolic appropriation of space to make room for arts-based initiatives, arts institutions function as the “colonizing arm”13 of gentrification. This is further reified through the role arts institutions have played in influencing urban planning decisions, such as the creation and modification of policies that fund, open and expand institutions in the hopes of catalyzing future development.14 As the racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic characteristics of neighbourhoods in New York City evolve over time, the policies, curation, and overarching goals of arts institutions evolve as well. This gives them the power to reflect neighbourhood change as well as to initiate it.

Arts institutions recognize and display this relationship in various ways, as seen materialized through different approaches to engagement and curation. That being said, all neighbourhoods are unique and so are their respective institutions; each represents its own unique interplay of particular histories, conflicts, tensions, vested interests and spatial complexities. As such, the particular influence that each arts institution has had and will continue to have as an agent of gentrification will vary significantly from institution to institution, neighbourhood to neighbourhood, and borough to borough.

Methodology

This research initiative prioritized the importance of not only studying and comparing drastically different institutions, but also the importance of experiencing and observing them first hand to grasp the nuances of social, cultural and institutional interactions that contribute to a shared and collaborative ethnography. The three prominent New York City institutions investigated were as follows: The MoMA PS1 in Long Island City, Queens; The Brooklyn Museum in the Crown Heights neighbourhood of Brooklyn; and The Frick Collection in the Lenox Hill neighbourhood of the Upper East Side of Manhattan.

To maximize the observations of the institutions during the relatively short 5 week collaborative internship with the Martin Prosperity Institute at the University of Toronto and The Urban Lab at the New York University Schack Institute of Real Estate, each case study comprised of site visits to the institution supplemented by an analysis following attendance at one of their major monthly events. For each visit, an ethnographic survey was completed about the content of the exhibits and the manner in which they were curated, the degree of physical and social integration and the accessibility achieved therein, along with observations on how families, individuals, and groups navigated and interacted with the spaces. This was followed by a comparison of the trends between the events and the standard visiting experience. The content and observations obtained through the ethnographic surveys were then analyzed thematically to inform a more contemporary and often uncaptured understanding of the identity of each institution. Demographic and socioeconomic data on community areas and census tracts supplemented the analysis of how each institution has potentially initiated or reflected neighbourhood change more generally, and gentrification more specifically.

Arts — Institution Spectrum

Through studying and comparing the three institutions, we discovered a blind spot in traditional anchor institution theory that views anchor-led neighbourhood change as a process with a uniform trajectory destined to enter end-stage gentrification.15 Instead, this report shows that institutional bodies have a high degree of influence and power to make active and conscious decisions that impact gentrifying and gentrified space. The institution itself is not a puppet of the greater forces of gentrification, but rather takes on the role of an agent by asserting the particular brand of neighbourhood change it wants to enact. These actions can be characterized by their particular curatorial and policy-oriented approaches, which differ greatly depending on the institution.

The following categories assist in understanding the various roles that an institution may play:

The MoMA PS1 assumes the identity of The Curator; similarly to how an art gallery selectively curates its exhibitions, as an institution it strives to selectively curate the particular demographic of individuals it hopes to attract driven by its own artistic mandate. The Frick Collection positions itself as The Relic whose identity is rooted in its sense of permanence and traditionalism as an integral part of a landmark neighbourhood of New York City. Contrarily, The Brooklyn Museum may be understood as The Reflector, as it reflects the voices and interests of the pre-existing communities whose narratives are challenged by new waves of settlement.

Arts institutions as agents of neighbourhood change should be understood on a spectrum of arts-led gentrification. This spectrum identifies the differences enacted by emerging institutions in gentrifying neighbourhoods, ranging from The Curator on one end of the spectrum to firmly established institutions in homogeneously affluent neighbourhoods, such as The Relic, on the other end. The two ends of the spectrum are bisected by particular institutions, such as The Reflector, whose very identity is informed by their role as a reflexive intermediary in a gentrifying neighbourhood.

These institutions are ones that have historically been witness to various waves of settlement and gentrification, though they act on their responsibility to provide an arena that accommodates both old and new residents in an effort to acutely reflect the contentious new reality of the neighbourhoods in which they are located. The Reflector as an institution is a venue of social and discursive disruption in the otherwise one-sided dialogue of neighbourhood change and gentrification. It is here that new and old voices consistently negotiate, push back, and collectively decide what the identity of a given institution — and more significantly, of the surrounding neighbourhood — will manifest itself as.

While there is a wide diversity of perspectives, information and ideas regarding gentrification theory, this spectrum seeks to refute some contemporary gentrification discourses that are inherently limited in their singular conception of institutions inevitably reaching end stage gentrification. This report illustrates a model whereby an institution that champions its reflexive position as an anchor in a transitional neighbourhood can exist validly amongst other institutions of similar status, while also successfully mediating the divides that emerge in gentrifying neighbourhoods.

MoMA PS1 — The Curator

Located in the emerging arts district in Long Island City, MoMA PS1, formerly known as P.S.1, is both a product and a producer of the region’s rapidly changing identity. Following the opening of the Queensboro Bridge at the turn of the 20th century, Long Island City transitioned from a farming community to a manufacturing center.16 As industrial work moved to developing countries, the region experienced significant deindustrialization which left behind several abandoned warehouses along the waterfront, turning the area into a ghost town by the mid-twentieth century.17 In 1971, Alanna Heiss, who had previously worked in London with the organization S.P.A.C.E 18 repurposing warehouses into arts spaces, saw the potential in converting the abandoned schoolhouse “P.S.1”19 into a dynamic, new arts space. For the next twenty years, the PS.1 Contemporary Art Space was used as a studio, performance, and exhibition center informed by radical curatorial decisions, which allowed a rotating group of artists — ranging from art-world celebrities to unknown up-and-comers — to reimagine and remodel the institutional space through long and short term installations.20 In 1997, the space underwent an $8.5 million renovation which included a redesigned entryway, 2-story exhibition space and outdoor gallery. Its facilities increased from 84,000 square feet to 125,000 square feet after reopening in 1997, making it the world’s largest institution dedicated to contemporary art.21

In 2000, the PS.1 Contemporary Art Space became an affiliate of the Museum of Modern Art as a way for the MoMA to keep a firm handle on the work of emerging artists.22 To celebrate the merger of the two institutions, the PS.1 Contemporary Art Space changed its name to MoMA PS.1 in 2010 to clarify the partnership between the two, officially providing an esteemed cultural designation in Long Island City and legitimizing its existence as an anchor.23 Within the overarching New York arts scene that prioritizes traditional and easily recognizable works of ‘high art’,24 MoMA PS1 has derived its identity by celebrating, sharing and promoting its distinctly DIY ethos through its prioritization of the contemporary, alternative and innovative above all else.

In the context of traditional discourse around gentrification, MoMA PS1 sits in an unusual position given exactly how it is influencing the anchor-led development occurring in its periphery. In 2001, rezoning in Long Island City allowed for the creation of higher density, mixed commercial and residential development which encouraged an increased emphasis on attractive, walkable streetscapes and improvements to main subway stops.25 This was combined with new tax and economic development incentives designed to both attract a highly desirable young, creative class of new migrants and encourage them to set down roots. In the summer of 2016, a New York Community Housing Authority Building had it lease revoked to make way for “creative tenants”.26 It is a move that provides further evidence of how Long Island City’s interest in creativity has influenced both how the built environment is developing, and exactly who it However, Long Island City has also historically been a Hispanic neighbourhood, representing 59% of the population in 2000 and 66% in 2016.27 Despite the embedded heritage of a visible existing community in the region, media reports that attempt to define the neighbourhood have continued to paint Long Island City as “empty” and an opportune location for young professionals who have been priced out of both Manhattan and now Brooklyn.28 The continued rhetoric insisting there is ‘nothing here’, as stated by one real estate broker who moved in 10 years ago, has also encouraged the influx of new commercial developments, as illustrated by burgeoning fashion and marketing industries. As an arts institution rooted in Long Island City, the main selling point for MoMA PS1 has long been centered around its ability to provide a ‘non-traditional’ space for new forms of expression and a reimagination of antiquated creative and organization processes. For new industries into the area, the flair of being associated with MoMA PS1 offers is a valuable marketing opportunity.

In this way, navigating through the physical space itself allows for further insight into some of the greater functions the institution is performing. While each exhibition offers an adequate amount of signage with the option for audio accompaniment, there is little direction in terms of how to engage with the institution as a whole. It is possible to make the argument that MoMA PS1 has been developed around a free-flowing, somewhat ‘flaneur’ style of movement. This not only challenges preconceived notions of how institutional gallery space is typically navigated but also encourages patrons to structure their own visit. It is a model that caters to individuals who desire an immersive and uniquely alternative arts experience that the MoMA PS1’s parent institution cannot offer. However, this model is not without sacrifice in two notable areas: a lack of accessibility and a highly securitized presence. The focus on installations in the stairwell, on the railings, under the landing, on the sides of the walls, and the highly prized long-term installation by Colette/Laboratoire Lumiere29 located in the attic, might be inaccessible to individuals who face mobility-related challenges. The museum’s online presence does little to prepare or make accommodations for individuals who cannot enter those spaces. While ongoing challenges with accessibility are issues that several institutions face, at the seemingly progressive MoMA PS1, it is a subtle action that speaks to a degree of insensitivity and avoidance of inclusivity. It furthers the belief that the institution prioritizes certain bodies, specifically those who are capable of experiencing all aspects of the institution and will likely engage further in paid services and events following a satisfactory experience.

Secondly, there was an extremely high volume of security personnel at the institution who nearly equalled if not outnumbered the patrons in certain installation rooms. During the site visit, they were vocal about seemingly non-descript behaviours such as staying at an otherwise empty installation for too long. Specific data on additional security roles aside from keeping order is not publicly available however their presence is in stark contrast to the other inherent values the institution claims to uphold in its mandate:

MoMA PS1 actively pursues emerging artists, new genres, and adventurous new work by recognized artists in an effort to support innovation in contemporary art. MoMA PS1 achieves this mission by presenting its diverse program to a broad audience in a unique and welcoming environment in which visitors can discover and explore the work of contemporary artists.30

The contrast between this mission statement and the highly controlled institutional environment highlights the fact that the “correct” behaviour of individuals is necessary for those entering the space. This is furthered by the identity and image that MoMA PS1 attempts to project, which fails to correspond with the reality of the neighbourhood. It still remains an unapologetically “adult” space that has been made inappropriate for children. It has failed to recognize the data highlighting the fact that Long Island City typically attracts permanent residents either before or shortly after they had their first child.31 This disconnect is seen in the absence of official children’s programming and the lack of child-friendly options for patrons attending events with children.

Its budding identity as a landing site for creative industries has inspired an aggressive cultural and spatial branding of which MoMA PS1 is the key informant. However, the influence of the arts on communities in the greater Long Island City region is not a new phenomenon. Until November 2014, 5-Pointz: The Institute of Higher Burnin’, which had become an international landmark of street art, sat in close proximity to MoMA PS132 — a visual reclamation of space from artists who did not qualify for entrance into the realm of the Museum. As the conversation shifts to the role MoMA PS1 plays in supporting spaces for local artists, these artists’ desire to look outside of their community and into larger national and international markets for talent supports existing literature about alternative arts spaces in the United States. Following WWII, alternative arts spaces operated under the mentality that performing local outreach meant opening up spaces for creativity while democratizing and decentralizing the attention often placed on arts pockets in homogenous, often affluent areas.33 The trade off for offering space enabled complete control over the creative direction and goals of the institution with little accountability to various stakeholders.

One of MoMA PS1’s few opportunities for engagement with local, creative groups is the bidding process for the design of their pivotal, new pavilion, which would provide an ample opportunity to present the work of local artists. Instead, it has historically gone to professional, established architecture firms like Escobedo Solíz Studio from Mexico City in 2016 and the Los Angeles based, Xefirotarch in 200534 who have a mutually beneficial relationship with MoMA PS1. These relationships allow creative firms capitalize on the weight of the MoMA PS1 brand while the institution increases its collaborations with a variety of interdisciplinary and creative individuals. Their fervent desire to be regarded as a monolith of alternative, institutional experimentation leaves little room for the open engagement of its actual commercial and It is here that MoMA PS1, as The Curator of the Long Island City neighbourhood, serves to externalize its pseudo-radical identity on the neighbourhood with the expectation that residents will mould their personal tastes and lives to successfully participate in an imagined reality created by the institution.

The Frick Collection — The Relic

The Frick Collection is located along the Museum Mile, one of the densest manifestations of culture in the world,35 on 5th Avenue and 70th Street in the Lenox Hill neighbourhood of the Upper East Side of Manhattan. As the widespread geographic imagination of the Upper East Side insists, it is an extremely wealthy area, with contemporary income distribution most commonly ranging from $100,000–$250,000. Less than a quarter of its population is non-white.36 The stable, homogenous nature of the Upper East Side, paired with the fact that it has consistently experienced sizable arts investment, makes the Frick Collection an important case study to investigate the power of arts institutions in contrast to other more dynamic areas of the city.

Prominent Pittsburgh industrialist Henry Clay Frick desired to build his own home in New York City to compete with his former business partner Andrew Carnegie who had one of the ‘grandest’ homes in New York City at 5th and 91st, which currently houses the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum.37 In 1906, he purchased the plot of land on which the museum presently stands which previously housed the Lenox Library, notoriously inaccessible to the public and on the verge of vacating before merging with the New York Public Library.38 Frick provided the New York Public Library with a $3 million monetary incentive for the Lenox heirs to give him the building rights.39 This trade-off was met with staunch public opposition that viewed “the Lenox Library as part of the fabric of Fifth Avenue”40 and Frick’s proposition to tear down the library and have it rebuilt stone for stone in Central Park was met with even stronger public outcry at the thought of losing park space. Tellingly, Frick retracted his plan, demolished the library, and constructed his mansion that would allow him to collect paintings that “reflected the high society into which he was moving.”41

Despite The Frick Collection’s status as one of the “few remaining Gilded Age mansions,”42 making it an important historic landmark for the history of City of New York, it also assumed the identity of memorializing Frick himself, who infamously proclaimed “I want this collection to be my monument.”43 It became one of the world’s best small museums,44 housing an impressive collection of European Old Masters like Bellini, Rembrandt, Vermeer, Gainsborough, Goya, Whistler, Van Dyck, Turner and El Greco. The adjacent Frick Art Reference Library founded in 1920 by Frick’s daughter Helen Clay Frick is now one of the leading institutions for research in art history and collecting.45 Despite the esteemed status of his private collection, Frick had long intended to leave the house to the public after his death, even providing a $15 million endowment to be used for maintenance, improvements, and additions in his will.46

The museum opened to the public in 1935 and continued to acquire works after Frick’s death, which account for about one third of the current works. Only those works that have been acquired after Frick’s death are eligible to be lent out and circulated,47 emphasizing the institutional permanence and The Relic identity of the Frick collection. The institution is curated “without regard to period or national origin”48 but rather according to Frick’s personal taste. The presentation of the works in The Frick Collection functions not to inform or educate visitors, but instead to relate artefacts to the highly marketable experience of reimagining the pomp of New York’s Gilded Age. As noted by the former director of The Frick Collection, Everett Fahy, “the extraordinary thing about The Frick is that it has always changed but all while giving the illusion that it’s the same.”49 As such, The Frick has rightfully earned its name as The Relic, as its selling point is rooted in its perceived permanence, citing its curatorial mission as “one of fine tuning rather than making major changes…without ruining what people love about it,” according to another former director, Samuel Sachs.50 To this point, John Russell Pope, the architect hired in 1933 aimed to avoid “the manner of exhibition common in museums”51 in an attempt to retain the original atmosphere of the house before it opened to the public in 1935, once again emphasizing the institution as a symbol rooted in preserving an individual past rather than a collective one.

It is important to note that this feeling of a past era is not experienced unanimously across age, racial and gendered lines but has also been the source of significant spatial tension and discomfort. For instance, The Frick has a strict policy that children under 10 are not allowed to enter the museum to protect fragile furniture and installations, which Sachs described as not “restrictive…it’s reasonable”52 — and in one sweeping policy decision managed to alienate an entire cohort of families with children just old enough to begin to comprehend and appreciate the collection for its artistic merit. Since the late 1990s, there has been directorial acknowledgement that there is a growing group of younger patrons who feel unwelcome at the institution. Sachs had responded with an interest in wanting to make “The Frick a more welcoming place for younger audiences while ensuring they not mess it up.”53 This kind of language posits that while visits from youth may be encouraged, their identity is inherently incompatible with the identity of The Frick. Furthermore, the youth that are actively deciding to visit The Frick are comfortable enough with their surroundings to navigate and seemingly engage with art in an institution that has limited signage. This presupposes a certain level of education, exposure, entitlement, and privilege in the types of crowds that The Frick is able to engage with and attract.

In fact, the notion of accessibility is not one extensively touched upon by the Frick aside from the use of multilingual audio-guides, increased internet presence and better signage.54 Its lack of formal acknowledgement of social inaccessibility through time remains evident today. During a regular visit to The Frick there was a high degree of behavioural policing, such as being told to not take photos and hang backpacks on one shoulder only. While most patrons seemed to be comfortable adhering to the institution’s policies, this was compounded with the fact that there was very little visible racial diversity in patrons, who were primarily white, while a large majority of the service personnel at the institution seen during the site visit were people of colour. During the free monthly event, there was more diversity in visitors along racial, gendered and age lines, who wandered through the building, sitting for free sketching sessions in the garden courtyard. Despite this orchestrated opening up of what is otherwise a fairly alienating institution, it did not correspond to an opening up of cultural and behavioural expectations. Instead, it reproduces the same dynamics of urban spatial politics in both traditional and contemporary New York.

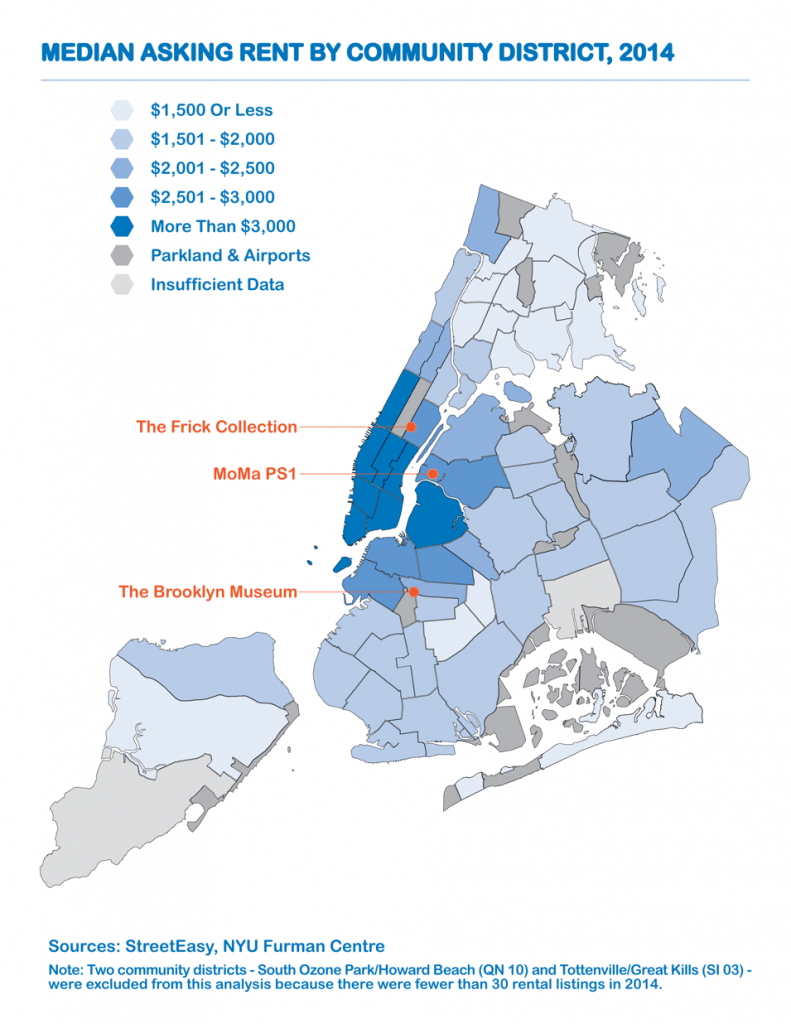

Similarly to how The Frick’s identity is rooted in its immutability, essentially reaching a plateau in dynamicism, the surrounding neighbourhood has also seemingly plateaued in character, with minimal ethnic and socioeconomic shifts from 2000 to 2014.55 Perhaps, when evaluating the responsiveness of The Frick, one could argue that it is in fact responsive and reflective of its relatively homogenous and affluent neighbourhood. Interestingly enough, this Relic identity may not be inevitably sustainable for The Frick as demonstrated in its history following a newly emerging influx of residents to the Upper East Side.56 In some parts of Brooklyn, soaring rent prices have priced people out of the market actually making the Upper East Side more affordable,57 which simultaneously offers the fact that it is “refreshingly devoid of bourgeois bohemianism.”58 In order to stay a relevant and dynamic member of the Museum Mile, the emergence of “Brooklyn’s newest refugees”59 may force The Frick to become more receptive and reflective of the younger, more diverse demographic, ultimately shaking how The Frick imagines and projects its identity. (See Figure 1)

The Brooklyn Museum — The Reflector

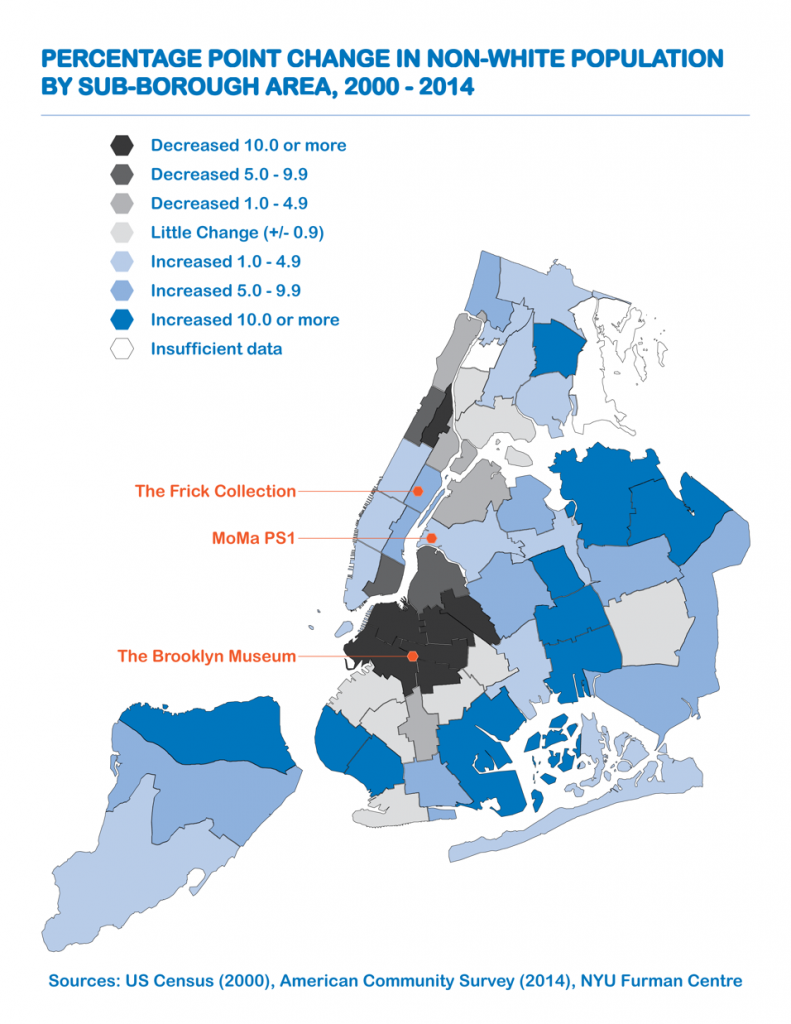

The Brooklyn Museum, located in the Crown Heights neighbourhood of Brooklyn, was born out of aspirations to transform the region into a neighbourhood competitive with some of the world’s grandest plazas.60 Since then, it has had to readjust its expectations to match the reality of the consistently evolving landscape. Initially conceived to be the largest museum in the world, in 1890, it intended to house the Brooklyn Children’s Museum, the Brooklyn Academy of Music, and the Brooklyn Botanical Garden.61 It was to become a centre for recreational, cultural and educational activity in the newly emerging Brooklyn, which at this point had been predominantly white.62 As the largest borough of New York and a former industrial hub, the surrounding region experienced a significant in-migration of black and Hispanic immigrants from Harlem following WWI as part of the ‘Great Migration.’63 As industries waned following the Second World War and the area fell into disrepair, gross civic disinvestment led to high concentrations of poverty triggering the flight of white residents out of Brooklyn into other areas of New York.64 (See Figure 2)

For two decades, preventative maintenance on the museum was neglected and in the 1930’s the original grand staircase was demolished to make way for an accessible, democratic ground floor entrance. The period between the 1950s and 1960s saw the institution struggling with significant budget shortfalls during which the institution as a whole fell into disrepair.65 Following the designation of the Brooklyn Museum as an official historic landmark in 1977,66 a design bid was launched for a long-term renewal expansion in 1986.67 With the appointment of curator Arnold L. Lehman in 1997, the Brooklyn Museum entered a new era: during his 17-year tenure Lehman would increase the Museum’s endowment from $53 million to $123 million, advocate for specific events for youth, minority groups and special needs individuals, and increase the museum’s private partnerships to ultimately bring in more revenue.68 During his time as curator he not only improved the economic position of the museum, but also informed a crucial new social mandate that sought to prioritize the identities of the individuals living in the Crown Heights neighbourhood.

In particular, his 1999 exhibition “Sensation: Young British Artists” from the Saatchi Collection came under significant fire for Chris Ofili’s work, “The Holy Virgin Mary” which stirred considerable controversy due to its depiction of the Black Madonna adorned with elephant dung.69 The reaction not only prompted Mayor Guiliani to deem the exhibition “un-Catholic” but initiated a lawsuit and threatened to remove its municipal funding — an amount of $7 million, a third of which comprised the museum’s total operating budget, if the work was not taken down.70 While the situation was resolved, two years later, the artist Renee Cox ran into similar controversy in 1999 for her Afro-Centric portrayal of the Last Supper featuring her nude body as Jesus Christ, which received similar outrage from Mayor Giuliani for violating decency standards.71

The period around the turn of the century also marked a rapid gentrification of Williamsburg and its surrounding neighbourhoods in Brooklyn, which included the in-migration of an incoming young and creative gentry.72 The Crown Heights neighbourhood in Brooklyn has emerged as a refuge for young, creative professionals who have been unable to afford renting both residential and commercial property in areas such as Williamsburg and Greenpoint. According to Christopher Havens, the head of the commercial division at AptsandLofts.com headquartered in Williamsburg, Crown Heights has “the fastest storefront turnover in the history of gentrification”73 which has positioned Crown Heights at the center of the “small manufacturing renaissance.”74

Around the time of the aforementioned intra-neighbourhood migration, The Brooklyn Museum entered into an era of renegotiation of itself alongside significant renovations to its built environment in order to repair its long-standing accessibility challenges.75 The Museum’s Beaux-Arts Court was rebuilt in 2001 and its skylight was restored to allow for community programming and events on the top floor of the Museum.76 In recent years, the Museum has redesigned several of its galleries to make them more accessible through bright wall colours, multimedia programming and an emphasis on flowing spaces. In 2004, the public plaza was completed as part of The Rubin Pavilion project to resolve particular issues with physical accessibility to the museum with an overall project cost of $63 million. It included numerous benches and the planting of cherry trees, and the construction of a “front stoop”, creating several sites for informal, public gatherings.77 The renovation is indicative of a commitment to both physical and social inclusiveness, in an attempt to weave together the different layers of humanity present in the immediate community. Also notable is the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art which opened in 2007, the first space of its kind in the country designed to display feminist art through a variety of different rotating and intersectional exhibits.78 The aforementioned curatorial decisions and intentional programming shift render The Brooklyn Museum a Reflector institution, due to its conscious efforts to reflect and prioritize the pre-existing, racialized residents, ensuring that their heritage is firmly engrained in the Museum’s current presence.

During the site-visit to the Museum’s monthly First Saturday’s event, the Museum demonstrated its innovative way of sharing the work of African-American, Hispanic and Indigenous visual artists. Throughout the evening, the event highlighted the Brooklyn Museum as an institution that refuses to be separated from its renewed commitment to advocating for its native community. A bartering table created by an Indigenous artist was intensely personal while also providing an example of alternative models of commerce. Elsewhere, a panel on challenges queer individuals face when immigrating to The United States, offered a forum of practical advice for individuals in the community. Possibly most impressive was the presence, and subsequent audience engagement, during the performance staged by The Theatre of the Oppressed, which used dramatic exercises to troubleshoot challenges that residents in the neighbourhood may experience when faced with discrimination and a lack of access to housing. The holistic programming was not only inspired by the geographic imagination of life in Brooklyn before its aggressive gentrification, but also underscored the fact that art spaces are inherently political.

Both explicitly and implicitly, the event made greater assertions on exactly which individuals were prioritized in the space: the native communities of people of colour, families with young children and older adults who could see themselves reflected in the programming. Lehman has been accused of pandering to “low-brow”79 tastes and failing to appropriately display some of the priceless works housed in the Museum. Such a critique offers insight into larger identity politics at play, not only regarding who is intended to engage with high art, but exactly what art they should be engaging with. It comments on the degree to which curatorial decisions, reflective of the native residents of the Brooklyn community, have a place in arts institutions of status in the their attempts to distance ‘the right to art’ from possessing economic capital.

During the standard visiting experience, the themes and notions mentioned above emphasized how the day-to-day visits to the Museum are as much catered to families, youth, racialized and minority groups as the First Saturday events. The Museum offers a family and child-friendly space in addition to a children’s learning and arts centre,80 which challenges the notion that children are incongruous with high art and their presence should be policed. The Museum clearly emphasizes teaching and education by way of the personal narratives and comprehensive signage presented in a clear, readable format throughout the space. The layout of the Museum is an important conditioning factor in teaching individuals who may not be familiar entering institutional spaces how they might extract value from the some of the works they’re engaging with. It is an action that delivers on the Museum’s mandate to bridge potential exposure and cultural barriers by considering how the pre-existing community may experience the space, which is representative of the Museum’s larger push for social accessibility.

These actions cannot be removed from the reality that the Brooklyn Museum remains situated in a rapidly gentrifying borough and its position to open and create space for pre-existing residents is not a neutral one. As the previous political controversies illustrated, the Brooklyn Museum can be understood as a site of conflict and a crossroads of cultures in tension between the new wave of gentrifiers and the native community. As such, it functions as an interactive arena of dialogue and reconciliation of Brooklyn’s past, present and future identities. It allows for the prioritization of narratives and needs of native residents as a deliberate and conscious effort to provide a marginally more equitable allocation of space in institutions that are notoriously uninclusive for such communities.

Conclusion

As one of the most ubiquitous characteristics of contemporary cities, it is nearly impossible to escape the explicit and implicit role that gentrification has had in shaping urban space. The significance of analyzing change through a spectrum provides an alternative to understanding this phenomenon as rigid and inevitable. Instead, the model of the spectrum highlights the need to emphasize mobility in conceptualizing gentrification. As neighbourhoods and their respective anchor institutions continue to change due to an ever-evolving interplay of forces, using a sliding scale to discuss neighbourhood transitions can be a helpful tool in remaining responsive to these changes over time. Where institutions will be positioned on the scale is determined by distinct policy and curatorial decisions. While this research initiative may identify MoMA PS1 as The Curator, The Frick Collection as The Relic and The Brooklyn Museum as The Reflector, similarly to how neighbourhoods themselves are never stagnant, these institutional identities are also not definitive.

Anchor arts institutions have an overwhelming capacity to dictate the character of the community, and for this reason, require a high degree of sensitivity when existing in areas that are being animated by arts-led neighbourhood change. As prominent anchor institutions, they must recognize their responsibility to be held accountable not only to tourists and admirers, but more importantly, to the immediate neighbourhood in which they are located in and interact with. It is essential that institutions both promote and advocate for a high degree of institutional reflexivity through ongoing consultation and engagement with neighbourhood groups. These directives may be achieved through the following recommendations:

- In order to ensure that all patrons can engage with the space to the best of their ability, arts institutions need to take active steps in improving physical accessibility in the built environment in order to match the standards set out by the Americans with Disabilities Act.81 They also should include a detailed, comprehensive description of any accessibility barriers the institution may have in highly visible physical and digital spaces.

- It is necessary to enforce affirmative action policies at all levels of creative, administrative and service oriented positions associated with the arts institution.

- The institution should look for opportunities to collaborate with local groups within the community in order to prevent limiting arts programming from existing solely within the walls of the institution itself.

- Institutions should create public forum venues where community members feel safe and welcome to voice their concerns — and community members should thus take a more active role in decisions being made.

- The City should appoint a representative advisory committee for each major arts institution, representative of the constituents of the surrounding neighbourhood to bring the concerns of the community to decision-making forums at these institutions.

- Upon the creation of municipal or institutional community forums, community members should actively seize the opportunity to voice their opinions, desires and queries regarding the programming, curation and management of the art institution.

Neighbourhood change does not have an inevitable destination. If every arts institution continued to enable pervasive gentrification, it would then enact such significant neighbourhood change that it would lead to the total displacement of native and newly settled lower-income residents out of vibrant urban centers altogether — consequently homogenizing the city, while subverting the very diverse and heterogeneous essence of urbanity.

Appendix

Figure 1: Median asking rent by community district, 2014

Sources: StreetEasy, NYU Furman Centre

Note: Two community districts — South Ozone Park/Howard Beach (QN 10) and Tottenville/Great Kills (SI 03) — were excluded from this analysis because there were fewer than 30 rental listings in 2014.

Figure 2: Percentage point change in non-white population by sub-borough area, 2000–2014

Sources: US Census (2000), American Community Survey (2014), NYU Furman Centre.

*Maps provided by the Martin Prosperity Institute.

References

1 Schulman, S. (2012). “The Dynamics of Death and Displacement” In The Gentrification of the Mind, 28-35. Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

2 Birch, E. (2010). Anchor Institutions and their Role in Metropolitan Change. Penn Institute for Urban Research, 1. Retrieved from http://penniur.upenn.edu/uploads/media/anchor-institutions-and-their-role-in-metropolitan-change.pdf. Accessed August 5, 2016.

3 Porter, M. (2010). Anchor Institutions and Urban Economic Development: From Community Benefit to Shared Value. Initiative for a Competitive Inner City. Retrieved from http://www.thecyberhood.net/documents/projects/icic.pdf.

5 Whyte, M. (2016). Soaring rent threatens Sterling Road’s creative vibe. Toronto Star. Retrieved from https://www.thestar.com/entertainment/visualarts/2016/01/31/some-sterling-road-artists-facing-steeper-rents-plan-to-move-on.html.

6 The United Nations. (2014). World Urbanization Prospects. Retrieved from https://esa.un.org/unpd/wup/Publications/Files/WUP2014-Highlights.pdf. Accessed August 5, 2016.

7 Artsy. (2015) “The 15 Most Influential Art World Cities of 2015”. Artsy + Planet Art. Retrieved from https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-contemporary-art-s-most-influential-cities.

9 Currid, E. (2006). “New York as a Global Creative Hub: A Competitive Analysis of Four Theories on World Cities.” Economic Development Quarterly. Retrieved from http://journals1.scholarsportal.info.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/pdf/08912424/v20i0004/330_nyaagcoftowc.xml

10 Artsy. (2015). “The 15 Most Influential Art World Cities of 2015.”

12 Brooks, A., Kushner, C., and Roland, J. (2002). “What Makes an Arts Capital: Quantifying a City’s Cultural Environment.” International Journal of Arts Management. Retrieved from file:///Users/melissavincent/Downloads/out%20(20).pdf.

13 Grodach, C., Foster, N. and Murdoch, J. (2014). Gentrification and the Artistic Dividend: The Role of the Arts in Neighborhood Change. Retrieved from https://www.arts.gov/sites/default/files/Research-Art-Works-Arlington2.pdf.

15 Grodach, C., Foster, N. and Murdoch, J. (2014). Gentrification and the Artistic Dividend: The Role of the Arts in Neighborhood Change. Retrieved from https://www.arts.gov/sites/default/files/Research-Art-Works-Arlington2.pdf.

16 Theodosiou, C., & Van Cura, D. (2009). Long Island City. The Greater Astoria Historical Society. Retrieved from http://astorialic.org/GAHS-LIC-Teachers-Guide.pdf. Accessed August 5, 2016.

17 Ouzounian, Richard, New York travel: Long Island City boasts great bars, museums and awesome views (Toronto Star, 2013).

18 “Significant Events in the History of MoMA PS1” last modified 2016. https://www.moma.org/learn/resources/archives/ps1_chronology.

19 “Significant Events in the History of MoMA PS1.”

20 Smith, R. (1997). Spacious and Gracious, Yet Still Funky at Heart. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/1997/10/31/arts/art-review-more-spacious-and-gracious-yet-still-funky-at-heart.html. Accessed August 5, 2016.

22 Vogel, C. (1999). A Museum Merger: The Modern Meets the Ultramodern. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/1999/02/02/arts/a-museum-merger-the-modern-meets-the-ultramodern.html. Accessed August 5, 2016.

23 Vogel, C. (2010). Tweaking a Name in Long Island City. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2010/04/30/arts/design/30vogel.html?_r=0. Accessed August 5, 2016.

24 Artsy. (2015) “The 15 Most Influential Art World Cities of 2015.”

25 “Long Island City Rezoning Proposal: Executive Summary.” (2001). New York City Government. Retrieved from https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/planning/download/pdf/plans/long-island-city-mixed-use/lic.pdf

26 Matua, A. (2016). New owner of LIC building that houses NYCHA offices won’t renew their lease and is looking for ‘creative’ tenants instead. QNS. Retrieved from http://qns.com/story/2016/07/27/new-owner-of-lic-building-that-houses-nycha-offices-wont-renew-their-lease-and-is-looking-for-tech-tenants-instead/. Accessed August 9, 2016.

27 NYU Furman Centre. (2016). “QUEENS: QNO2 Jackson Heights” In State of New York City’s Housing & Neighbourhoods — 2015 Report, 117. Retrieved from http://furmancenter.org/files/sotc/Part_3_SOCin2015_9JUNE2016.pdf. Accessed July 30, 2016.

28 Jacobson, A (2016) Long Island City: Fast-Growing with Great Views. New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/14/realestate/long-island-city-fast-growing-with-great-views.html Accessed August 2, 2016.

29 Colucci, E (2016) Not an Alternative: “FORTY” at MoMA PS1. Artfcity. Retrieved from http://artfcity.com/2016/07/13/not-an-alternative-forty-at-moma-ps1/. Accessed August 14, 2016.

30 “Mission Statement.” (2016). MoMA website PS1. Retrieved from https://www.moma.org/about/index

31 Jacobson, A. (2016). Long Island City: Fast-Growing with Great Views.

32 Holpuch, A. (2014). New York’s graffiti mecca 5 Pointz torn down. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2014/aug/22/5-pointz-new-york-graffiti-torn-down. Accessed August 5, 2016.

33 Hertz, B. (2001). The Independent Wedge: A Brief History of Alternative Exhibition Spaces in the United States with Case Studies from New York City. Art Factories. Retrieved from http://www.artfactories.net/The-Independent-Wedge-A-Brief.html?gt. Accessed on August 7, 2016.

34 Young Architects Program. (2016). MoMA PS1. Retrieved from http://momaps1.org/yap/. Accessed August 2, 2016.

35 “Museum Mile, New York City”. (2016). NY.com. Retrieved from https://www.ny.com/museums/mile.html

36 NYU Furman Centre. (2016). “City, Borough, and Community District Data” In State of New York City’s Housing & Neighbourhoods — 2015 Report, 117. Retrieved from http://furmancenter.org/files/sotc/Part_3_SOCin2015_9JUNE2016.pdf. Accessed July 30, 2016.

37 Nevius, J. (2014). The Controversial Origins of New York City’s Frick Collection. Curbed New York. Retrieved from http://ny.curbed.com/2014/7/29/10068128/the-controversial-origins-of-new-york-citys-frick-collection. Accessed August 5, 2016.

42 “History.” (2016). The Frick Collection. Retrieved from http://www.frick.org/collection/history. Accessed August 5, 2016.

43 Nevius. (2014). The Controversial Origins of New York City’s Frick Collection.

44 “History” (2016). The Frick Collection.

49 Vogel, C. (1998). Director Tries Gentle Changes For the Frick. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/1998/09/07/arts/director-tries-gentle-changes-for-the-frick.html. Accessed August 5, 2016.

51 Nevius. (2014). The Controversial Origins of New York City’s Frick Collection.

52 Vogel, C. (1998). Director Tries Gentle Changes For The Frick.

54 Rosenau, H. (1998). Accessibility of The Frick Collection Greatly Enhanced. Archived Press Release from The Frick Collection. Retrieved from http://www.frick.org/sites/default/files/pdf/press/Accessibility.pdf. Accessed August 5, 2016.

55 NYU Furman Center. (2016). City, Borough, and Community District Data.

56 Kaufman, J. (2014). For Starters, the Upper East Side. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2014/03/16/realestate/for-starters-the-upper-east-side.html?_r=0. Accessed August 5, 2016.

58 Fishbein, R. (2014). Let’s All Move To The Upper East Side! Gothamist. Retrieved from http://gothamist.com/2014/09/02/upper_east_side_hip.php. Accessed August 5, 2016.

60 “Profile: Brooklyn Museum”. (2016). New York Magazine. Retrieved from http://nymag.com/listings/attraction/brooklyn-museum-of-art/. Accessed August 5, 2016.

61 The Brooklyn Museum. (2015). Brooklyn Museum Building: A Brief History of one of the Oldest and Largest Arts Institutions in the United States. The Brooklyn Museum. Retrieved from https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/features/building. Accessed August 5, 2016.

63 New York Public Media. (2016). “History of Brooklyn.” PBS Thirteen. Retrieved from

http://www.thirteen.org/brooklyn/history/history3.html. Accessed August 5, 2016.

64 Gregor, A. (2015). Crown Heights, Where Stoop Life Still Thrives. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2015/06/21/realestate/crown-heights-brooklyn-where-stoop-life-still-thrives.html. Accessed August 5, 2016.

65 “Brooklyn Museum Building.” (2015). The Brooklyn Museum.

68 Vogel, C. (2014). Brooklyn Museum’s Longtime Director Plans to Retire. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2014/09/10/arts/design/arnold-lehman-to-step-down-from-his-post.html?_r=0. Accessed August 5, 2015.

69 The Art of Controversy. (1999). PBS. Retrieved from http://www.pbs.org/newshour/bb/entertainment-july-dec99-art_10-8/. Accessed July 23, 2016.

71 Williams, M. (2001). Yo Mama Artist Takes on Catholic Critic. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2001/02/21/nyregion/yo-mama-artist-takes-on-catholic-critic.html Accessed August 5, 2015.

72 Zimmerman, E. (2014). Creative class migrates deeper into the boroughs. Crains. Retrieved from http://www.crainsnewyork.com/article/20140722/SMALLBIZ/140729964/creative-class-migrates-deeper-into-boroughs. Accessed August 5, 2016.

75/a> “Brooklyn Museum Building.” (2015). The Brooklyn Museum.

79 Vogel, C. (2014). Brooklyn Museum’s Longtime Director Plans to Retire.

80 “Gallery Studio Schedule for Children and Teens.” (2016). The Brooklyn Museum. Retrieved from https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/education/youth-and-families/gallery_studio_schedule. Accessed August 3, 2016.

81 Department of Proposed Changes in ADA Regulations in Design Standards. (2008). U.S. Department of Justice: Civil Rights Division. Retrieved from https://www.ada.gov/newsltr0808.htm. Accessed on August 11, 2016.

Works Cited

Artsy. (2015). “The 15 Most Influential Art World Cities of 2015.” (2015). Artsy + Planet Art. Retrieved from https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-contemporary-art-s-most-influential-cities.

Birch, E. (2010). Anchor Institutions and their Role in Metropolitan Change. Penn Institute for Urban Research. Retrieved from http://penniur.upenn.edu/uploads/media/anchor-institutions-and-their-role-in-metropolitan-change.pdf. Accessed August 5, 2016.

The Brooklyn Museum. (2015). Brooklyn Museum Building: A Brief History of one of the Oldest and Largest Arts Institutions in the United States. Brooklyn Museum. Retrieved from https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/features/building. Accessed August 5, 2016.

Brooks, A., Kushner, C., and Roland, J. (2002) “What Makes an Arts Capital: Quantifying a City’s Cultural Environment.” International Journal of Arts Management. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/stable/41064773

Colucci, E. (2016). Not an Alternative: “FORTY” at MoMA PS1. Artfcity. Retrieved from

http://artfcity.com/2016/07/13/not-an-alternative-forty-at-moma-ps1/. Accessed

August 14, 2016.

Currid, E. (2007). “How Arts and Culture Happen in New York: Implications for Urban

Economic Development.” Journal of American Planning Association. Retrieved from http://tinyurl.com/hgb56g4.

Currid, E. (2006). “New York as a Global Creative Hub: A Competitive Analysis of Four

Theories on World Cities.” Economic Development Quarterly. Retrieved from http://journals1.scholarsportal.info.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/pdf/08912424/v20i0004/330_nyaagcoftowc.xml.

Department of Proposed Changes in ADA Regulations in Design Standards. (2008). U.S. Department of Justice; Civil Rights Division. Retrieved from https://www.ada.gov/newsltr0808.htm. Accessed on August 11, 2016.

Fishbein, R. (2014). Let’s All Move To The Upper East Side! Gothamist. Retrieved from http://gothamist.com/2014/09/02/upper_east_side_hip.php. Accessed August 5,

2016.

Gallery Studio Schedule for Children and Teens. (2016). The Brooklyn Museum. Retrieved from https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/education/youth-and-families/gallery_studio_schedule. Accessed August 3, 2016.

Gregor, A. (2015). Crown Heights, Where Stoop Life Still Thrives. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2015/06/21/realestate/crown-heights-brooklyn-where-stoop-life-still-thrives.html. Accessed August 5, 2016.

Grodach, C., Foster, N. and Murdoch, J. (2014). Gentrification and the Artistic Dividend: The Role of the Arts in Neighborhood Change. Retrieved from https://www.arts.gov/sites/default/files/Research-Art-Works-Arlington2.pdf

“History.” (2016). The Frick Collection. Retrieved from

http://www.frick.org/collection/history. Accessed August 5, 2016.

Holman, K (1999) The Art of Controversy. Public Broadcasting Service. Retrieved from

http://www.pbs.org/newshour/bb/entertainment-july-dec99-art_10-8/. Accessed July 23 2016.

Holpuch, A. (2014). New York’s graffiti mecca 5 Pointz torn down. The Guardian. Retrieved

from https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2014/aug/22/5-pointznewyork-graffiti-torn-down. Accessed August 5, 2016.

Jacobson, A. (2016). Long Island City: Fast-Growing with Great Views. The New York Times. Retrieved from

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/14/realestate/long-island-city-fast-growing-with-great-views.html. Accessed August 2, 2016.

Kaufman, J. (2014). For Starters, the Upper East Side. The New York Times. Retrieved from

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/03/16/realestate/for-starters-the-upper-east-side.html?_r=0. Accessed August 5, 2016.

Kaysen, R. (2016). Price and Proximity Draw Fashion Industry to Long Island City. The New York Times. Retrieved from

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/06/22/realestate/commercial/price-and-proximity-draw-fashion-industry-to-long-island-city.html. Accessed August 9, 2016.

“Long Island City Rezoning Proposal: Executive Summary” (2001). New York City Government. Retrieved from https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/planning/download/pdf/plans/long-island-city-mixed-use/lic.pdf.

Matua, A. (2016). New owner of LIC building that houses NYCHA offices won’t renew their lease and is looking for ‘creative’ tenants instead. QNS. Retrieved from http://qns.com/story/2016/07/27/new-owner-of-lic-building-that-houses-nycha-offices-wont-renew-their-lease-and-is-looking-for-tech-tenants-instead/. Accessed August 9, 2016.

“Museum Mile, New York City”. (2016). NY.com. Retrieved from https://www.ny.com/museums/mile.html.

Nevius, J. (2014). The Controversial Origins of New York City’s Frick Collection. Curbed New York. Retrieved from

http://ny.curbed.com/2014/7/29/10068128/the-controversial-origins-of-new-york-citys-frick-collection. Accessed August 5, 2016.

New York Public Media. (2016). “History of Brooklyn”. PBS Thirteen.Retrieved from

http://www.thirteen.org/brooklyn/history/history3.html. Accessed August 5, 2016.

NYU Furman Centre. (2016). Queens: QNO2 Jackson Heights” In State of New York City’s Housing & Neighbourhoods — 2015 Report, 117. Retrieved from http://furmancenter.org/files/sotc/Part_3_SOCin2015_9JUNE2016.pdf. Accessed July 30, 2016.

NYU Furman Centre. (2016). “City, Borough, and Community District Data” In State of New York City’s Housing & Neighbourhoods — 2015 Report, 117. Retrieved from http://furmancenter.org/files/sotc/Part_3_SOCin2015_9JUNE2016.pdf. Accessed July 30, 2016.

Ouzounian, R. (2013). New York travel: Long Island City boasts great bars, museums and awesome views. Toronto Star, 2013.

Porter, M. (2010). Anchor Institutions and Urban Economic Development: From Community Benefit to Shared Value. Initiative for a Competitive Inner City. Retrieved from http://www.thecyberhood.net/documents/projects/icic.pdf.

“Profile: Brooklyn Museum.” (2016). New York Magazine. Retrieved from http://nymag.com/listings/attraction/brooklyn-museum-of-art/. Accessed August 5, 2016.

Rosenau, H. (1998). Accessibility of The Frick Collection Greatly Enhanced. Archived Press Release from The Frick Collection. Retrieved from http://www.frick.org/sites/default/files/pdf/press/Accessibility.pdf. Accessed August 5, 2016.

Rosenau, H. (2014). The Frick Collection Announces Plan to Enhance and Renovate its Museum and Library. Archived Press Release from The Frick Collection. Retrieved from http://www.frick.org/sites/default/files/pdf/press/Announcement2014_Release_ARCHIVED.pdf. Accessed August 5, 2016.

Schulman, S. (2012). “The Dynamics of Death and Displacement” In The Gentrification of the Mind, 28–35. Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

“Significant Events in the History of MoMA PS1” (2016). MoMA PS1 Chronology. Retrieved from https://www.moma.org/learn/resources/archives/ps1_chronology. Accessed August 5, 2016.

Smith, R. (1997). Spacious and Gracious, Yet Still Funky at Heart. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/1997/10/31/arts/art-review-more-spacious-and-gracious-yet-still-funky-at-heart.html. Accessed August 5, 2016.

Theodosiou, C., & Van Cura, D. (2009). Long Island City. The Greater Astoria Historical Society. Retrieved from http://astorialic.org/GAHS-LIC-Teachers-Guide.pdf. Accessed August 5, 2016.

The United Nations. (2014). World Urbanization Prospects. Retrieved from https://esa.un.org/unpd/wup/Publications/Files/WUP2014-Highlights.pdf. Accessed August 5, 2016.

Vogel, C. (1999). A Museum Merger: The Modern Meets the Ultramodern. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/1999/02/02/arts/a-museum-merger-the-modern-meets-the-ultramodern.html. Accessed August 5, 2016.

Vogel, C. (1998). Director Tries Gentle Changes For the Frick. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/1998/09/07/arts/director-tries-gentle-changes-for-the-frick.html. Accessed August 5, 2016.

Vogel, C. (2010). Tweaking a Name in Long Island City. The New York Times. Retrieved from

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/04/30/arts/design/30vogel.html?_r=0. Accessed August 5, 2016.

Vogel, C (2014). Brooklyn Museum’s Longtime Director Plans to Retire. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2014/09/10/arts/design/arnold-lehman-to-step-down-from-his-post.html?_r=0. Accessed August 5, 2015.

Whyte, M. (2016). Soaring rent threatens Sterling Road’s creative vibe. Toronto Star. Retrieved from

https://www.thestar.com/entertainment/visualarts/2016/01/31/some-sterling-road-artists-facing-steeper-rents-plan-to-move-on.html.

Williams, M. (2001). Yo Mama Artist Takes on Catholic Critic. The New York Times. Retrieved from

http://www.nytimes.com/2001/02/21/nyregion/yo-mama-artist-takes-on-catholic-critic.html. Accessed August 5, 2015.

Young Architects Program. (2016). MoMA PS1. Retrieved from http://momaps1.org/yap/. Accessed August 2, 2016.

Zimmerman, E. (2014). Creative class migrates deeper into the boroughs. Crains. Retrieved

from http://www.crainsnewyork.com/article/20140722/SMALLBIZ/140729964/creative-class-migrates-deeper-into-boroughs. Accessed August 5, 2016.